So… Last week I was in Tallinn and was able to follow the launch of the new TV series based on Grossman’s Life and Fate. I had heard previously that this was happening, and was worried already then. I love the book and it is a tough one to dramatise, just because of its size and the amount of characters, to mention just one obvious difficulty. It is that common thing of: “What did you think of the film?” “Oh I prefer the book…” So I was wondering what would happen. One serious flaw of this review is that I haven’t finished watching the series yet, so can only comment up to the last few episodes.

As I spent the last four years writing my PhD on the novel and know it pretty well by now, everyone says that it is natural that I won’t like the film because, inevitably, it won’t be like the novel. I am too biased to have an honest opinion of it. I will admit that the book is precious to me and any rendering of it is always something that I anticipate with some dread. However, I was equally ready to find a good film of the book so that I could share its treasures with people more easily (rather than suggesting they read the 700 page epic or forcing them to listen me reading passages from the book, not the best experience). But, as you can tell, I was disappointed with the series. Why?

I concede that some revision is necessary to bring a book to the screen, but some of the rewriting of the events and the dialogue removed the series too far from the book. It seems that the writer/director fuses For a Just Cause with Life and Fate, which I think is not a bad idea, but the way that it is done has re-arranged the events quite substantially. (I am talking here of Tolya, who is DEAD in Life and Fate, but has a very different role in the film – I’m trying to not give too much away here if you should want to see it.)

Also, I know that the book is about the battle of Stalingrad, but it seems to me that the filmmakers focused exclusively on war and battles. What makes Grossman’s novel amazing (and his wartime articles), is the fact that he goes beyond the war and depicts people, personalities and relationships. He sees the man in war, his fears, his hopes, his vulnerabilities. In the film, it is the fighting itself that takes center stage. There is blood, explosions, dirt and a great amount of vodka. In order to make a moment meaningful the director just puts some loud violin over it and we’re supposed to feel touched. Of course, it is a film and Grossman’s words need to be represented audiovisually, but the subtlety of human relations is lost in the film. I suppose this could be proof of the power of words, that perhaps they can touch us more than imagery. But it also makes me wonder whether it is an attempt at pacifying the messages in the novel, removing the very reasons for which it was arrested in 1961. Is that really freedom for the novel in the 21st Century Russia?

Another very typical problem with dramatisations is the choice of actors for characters. Often we get disappointed because they never look like what we imagine them to be like. Or the actors replace our personal idea of the character completely, who can think of Mr. Darcy without imagining Colin Firth? I can’t, and to be honest, I don’t want to. As expected, I do not agree with some of the choices of actors for this film. But one thing I really liked was the choice of Sergey Makovetsky as Shtrum. This is because he looks remarkably like Grossman, and considering Shtrum was based on Grossman, this was a good choice indeed. It points to the relationship between the author and the novel, without making an obvious statement.

Shtrum and Marya Ivanovna in the film

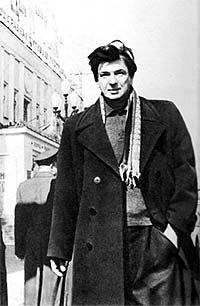

Grossman at Stalingrad

Shtrum

Krymov I felt didn’t look like what I imagined him in the book (especially because he reminded me of a serious and slightly slimmer version of Dara O’Briain), but I wasn’t too disappointed with that, it is to be expected.

Krymov

I always imagined Krymov to be dark haired and severe looking, a bit more like the director’s choice for Novikov, played by Evgenii Dyatlov.

Novikov

This was perhaps the choice that I was least pleased with. To me, Novikov is a bit of a softer character than the man above, but that is my impression. Otherwise, the choices of women was generally very good. Zhenya, played by Polina Agureeva, and Lyudmila, played by Lika Nifontova, were both good choices I think, and good actresses.

Zhenya

Lyudmila

Overall, I got bored watching the film, which just seems unbelievable considering how much I love the book. I was touched by the scene of Lyudmila at Tolya’s grave, but otherwise felt that I never came close to the characters. I just couldn’t feel that I understood or cared for them. There is also a narrator in the film, reading passages from the novel, but even his voice sounds dull and tired. Considering he is narrating war, one can understand that the voice has to be sombre to an extent, but what makes Grossman’s novel so amazing is the light that permeates the whole narrative. In the end human spirit, freedom, love and an inner light, all survive and that is the ultimate message. This seems to me to be missing from the film completely. I may change my mind as I finish watching it, but having seen as far as Film 4 Episode 2 and having only four episodes left, I have little hope….

P.S. So far, there is no depiction of camps and thus Ikonnikov’s discussions of Good and Evil, so there you go.